September 2018. A long weekend was coming up. All four of us (Dad, Mom, Big Sis and I) happened to not be busy or working that weekend. A rare occurrence. Between Dad (always down for driving long distances) and Mom (always ready to go home to visit her father…as long as she didn’t have to do any driving) it was decided: we needed to visit Mkhulu[1].

And so it came to pass, that we found ourselves on the N3 from Pretoria to KwaZulu-Natal that Saturday morning. It was a good trip with smooth roads. Dad kept drawing our attention to the gazillion herds along the way (“Look! The last ones were looking to the left. These cows are looking to the right!” Repeat, but with sheep.) The fire (fire![2]) playlist was interspersed with hilarious episodes of a certain podcast (namely, Jesus and Jollof. Mom would often ask later for more episodes with “those two funny Nigerian ladies”.) There might also have been scones.

In the spirit of the long weekend, we took our sweet time during our lunchtime pitstop at Harrismith, one of the highlights of which was Dad telling us about his dream of facing off with a lion…Yeah. Hence, it took us a while to reach the land of the sugarcane. We arrived eKwaZulu late on Saturday afternoon, necessitating a sleep-over in Ballito.

Sunday morning, we drove the last 2 hour stretch to the family home, the last 45 minutes of which were spent negotiating a thousand hills and valleys of rain-rivetted gravel road. At last, we spotted Gcotsheni, as we called the grandparents’ pink house[3], at around tea time a.k.a. church time.

When the car finally rolled up to the gate, Keeper[4], Mkhulu’s latest canine companion, bounded to the gate to loudly announce his master’s unexpected guests. His duty.

As far back as I can remember, Mkhulu had kept dogs. Sometimes Rottweilers, sometimes Boerboels. Almost always a pair: male and female. Always outside dogs, kept for the sole purpose of guarding the homestead. Or so I thought. Keeper, Mkhulu’s only dog at the time, was a Boerboel. Or was he an Africanis mix? It’s anyone’s guess. Regardless. Keeper had the large build Mkhulu favoured in his dogs, but he was well-trained; he backed down immediately once he knew that we were welcomed guests. I like to think that he took one good look at my mother’s forehead and thought to himself, “Aah. She is one of my master’s people. I will grant her entrance.”[5]

Mkhulu was pleasantly surprised by the Gauteng branch’s sudden appearance. I had always thought of Life eGcotsheni as peaceful, free from the noise and pollution of the Tshwanes and Jozis. But I recognise now that it could be extremely lonesome, especially for one who had been recently widowed after more than 60 years of marriage. It had been around a year and a half since my Gogo[6] had passed. And more than a year since Mkhulu had been convinced that he was soon to follow.

For someone soon to follow, he looked really healthy. A little slower in movement, but still standing proud. The quintessential strong silent type.

We were welcomed into the sacrosanct, carpeted living room, where Mkhulu sat in repose, in His Chair, bell close at hand on a nearby tray table. The housekeepers who kept the house in order, helped Mom, Big Sis and I to lay out the refreshments in the kitchen (we of course did not arrive empty-handed; that was the purpose of the Ballito stop). Every now and then, Keeper would pop his head in the kitchen from outside, and try to sneak a paw past the threshold. He would retreat when he noticed us noticing him.

Back in the living room, the parentals asked after Mkhulu’s health, any news updates, etc.

Mkhulu’s news: his friend Bab’Shandu visited him often, and although physically going to church was no longer an option, he could listen in to the Lutheran broadcasts on radio (still playing in the background). He asked how we were doing. We gave our summarised life updates in turn (in order of seniority, you understand). My turn came.

“Mzukulu[7], why are you so pale?” was Mkhulu’s first question. (Answer: because I never saw the sun, what with working in a fluorescent environment all day).

“What do your students and juniors say about being taught by a person as young as you are?” was his second question. To him, I probably still looked like a newborn, or a toddler at best. (Voiced Answer: it was challenging. Unvoiced Answer: an intensely awkward dynamic; in fact, I was in the process of jumping the academic ship[8]).

While we were thusly occupied shooting the proverbial breeze, Keeper had managed to sneak past the ladies in the kitchen, and had trotted, quite softly considering his size, into the living room. The Sacrosanct. Carpeted. Living Room.

I need to pause and explain something here. Ours is a large family. Any time we converged eGcotsheni for family events, the bulk of our life activities were restricted to the kitchen or outside. The living room was for my grandparents, honoured guests and family prayers. And when we, the family, came in to deliver meals to the grandparents or for said evening prayer time, shoes were strongly discouraged in the living room.

The dog was walking into THAT living room. I was scandalised, but I was not about to reprimand Mkhulu’s Dog. As I continue.

Keeper kept a wide berth around us, strangers as we were to him, went behind the sofas and around, coming to a stop at Mkhulu’s side. Mkhulu patted his head, and told him, “Usungibonile manje. Ungaphuma ke.”[9] Calmly, in conversational tones. Like a boss.

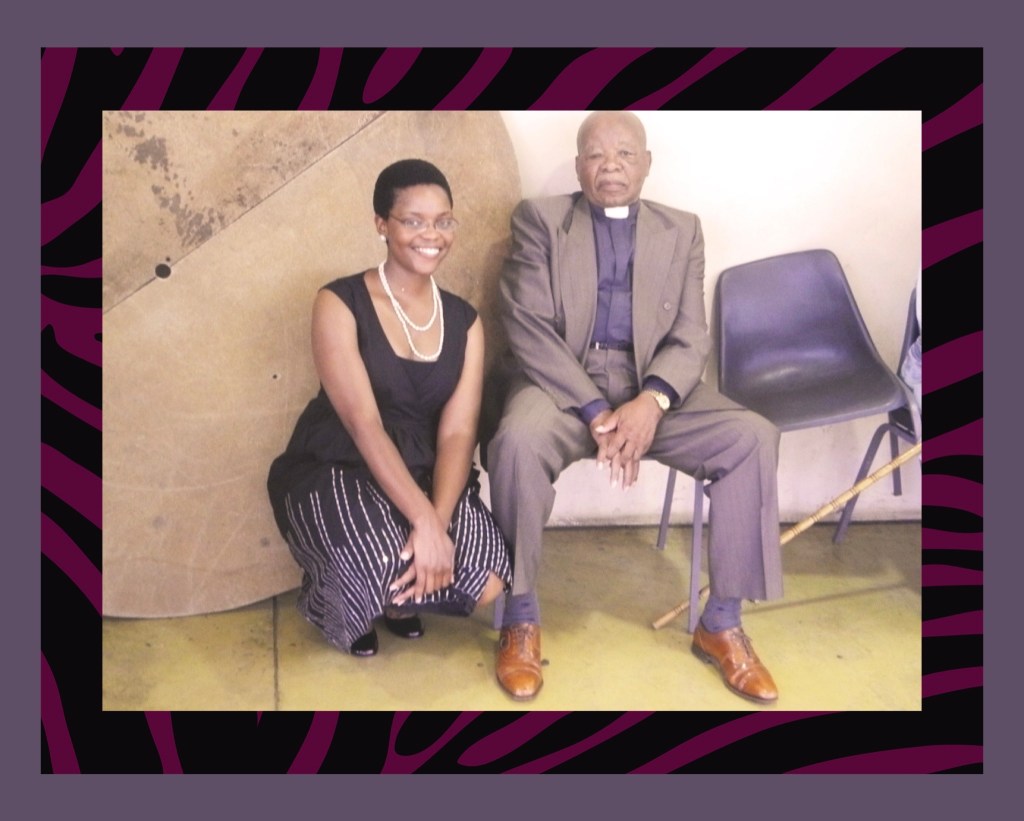

That was C.S. Ntuli[10]. Steady. Authoritative. Warm, yet firm. Gifted with the written word, yet economical with the spoken. A man of few words, he said much, without saying much. Mkhulu, in addition to being a prolific isiZulu author and poet, was a lifelong educator. He later became a minister in the Lutheran church. In other words, when he spoke, everybody under the sound of his voice listened. He was a man who commanded respect in all he did. And his canine companion knew it too.

Keeper left immediately, his job of checking on his master complete[11].

Another layer was added that very day to the mountain of respect I had for my Mkhulu. One thing we had in common, besides a love for the written word, was a love for dogs. My two dogs had never—NEVER—listened to any of my commands. Mkhulu spoke just two sentences. And it was done. Again I say: Boss.

Mkhulu was the embodiment of the strong, rock-solid, seemingly immovable patriarch. And, might I add, looking really good for an 87-year-old. Actually, looking good, nje.

So when, 2 months later, Mom called to tell me Mkhulu had passed away, I said something inane like, “My Mkhulu?”, as my brain struggled to interpret the data entering my ears[12]. She confirmed that my Mkhulu, her father, had gone to be with the Lord.

The first weekend of December, we travelled back to the family home for Mkhulu’s homegoing. Our patriarch was gone, and with his passing came a seismic shift in our family, even more than when my grandmother passed on. Mkhulu had been the pillar of our family, stoically looking after his wife, his children (Mom and her siblings), being concerned about their spouses (Dad, and my aunties and uncles) and us, the grandchildren. Leading us consistently in prayer and preaching the Word of God[13].

There were fewer numbers present at his funeral, compared with my grandmother’s the year before; and that allowed us the space to reflect on the completion of our grandparents’ time on earth. To celebrate his life. To grieve as we needed to, without the undue pressure to dish up the ‘right’ amount of rice or butternut for lines and lines of mourners, or no rice for those following a no-carb diet[14].

Mkhulu was laid to rest next to my grandmother, close to his parents, and two of his sons. On a hill overlooking a thousand valleys. We miss him.

Do you know who else clearly missed him? Keeper.

The morning after the funeral, one of my younger cousins was instructed to feed Keeper his breakfast. But he wasn’t outside the kitchen. In fact, it seemed no-one at the main house had seen him that morning. Eventually, one of my uncles came in and reported that he had found him.

Keeper was sitting next to Mkhulu’s freshly covered grave. Keeping watch at his master’s side.

He was never quite the same without his master. Despite his fearsome appearance, he was actually quite shy of crowds, preferring to keep to himself. Occasionally, he would sit close to one or the other of my cousins, especially if the chosen cousin possessed the trademark isiphongo[15] of C.S. Ntuli’s descendants.

But he was never quite the same.

April 2023. One of my uncles broke the news that Keeper had become ill. The vet said it was cancer, and that Keeper would need to be put down. That faithful guard of my late grandfather’s home and final resting place, had come to the end of his canine life. My cousin, the spitting image of Mkhulu, was the one tasked with accompanying Keeper in his final moments.

Keeper’s final job, the one he doesn’t know he had[16], was to allow me to risk opening grief’s floodgates, and to gently meander down a padded path of remembrance. A gatekeeper to the last. I finally have the words to start writing about my grandfather, five years later. I remember my Mkhulu, his deep voice when singing hymns and preaching, him sitting in His Chair, him calmly keeping order in the family. I remember him dressed to the nines at family functions, and him taking a stroll through the house to make sure we noticed how sharp he looked. I also remember him and my own Dad, one of his sons by marriage, and how they enjoyed each other’s company. I will remember that September as one of the last road-trips we took as a family. It was a good trip.

Good job, Keeper.

©Copyright Gugulethu Mhlanga 2023.

[1] Grandfather

[2] Curated by yours truly, of course.

[3][3] Technically, the entire area is called Gcotsheni, but we cheat and call the house Gcotsheni, which means The Place of Anointing.

[4] Short for Gatekeeper

[5] I know. Dogs are not known for complex thought processes. But I really think that was Keeper’s thinking. That forehead is hereditarily unmistakeable.

[6] Grandmother

[7] Mzukulu means grandchild

[8] That’s a story for another day

[9] Translated: “You’ve seen me now. You can go out.”

[10] C.S. Ntuli: if I started getting into the entirety of my Mkhulu’s life, I would end up writing an entire book. Should I?

[11] Mkhulu explained that our visit had interrupted Keeper’s routine of regularly checking in with Mkhulu, which is why he became antsy and walked into the living room.

[12] Grief and shock have a way of removing logical thought processes. Or is it just me?

[13] Whether you personally believed and obeyed Jesus was between you and God, but in Mkhulu’s house, the family prayed. No correspondence entered into.

[14] As for Banting emakhaya at another family’s funeral.

[15] Forehead

[16] As much as a dog can know anything

Leave a comment